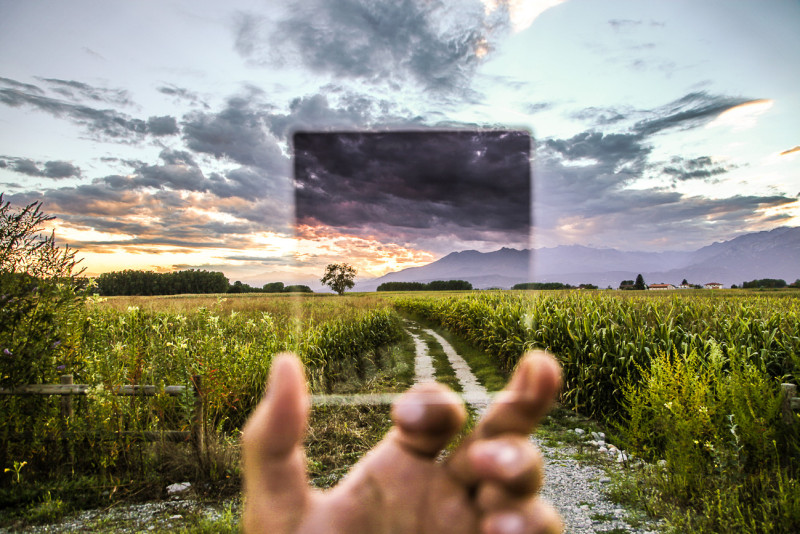

Can you really know what you like or dislike if you haven’t experienced ‘it’?

We like to think we can, and often, we convince ourselves that we have the answers for questions to what we ‘should’ be or ‘want’ to be doing for our careers. But when this vision is finally realized, the expectation of excitement and fulfillment is nowhere to be found.

There’s a good explanation for this feeling or lack thereof: the importance of the ‘it’ too often is overlooked; stripped of its magic as we are conditioned (by the education system) to use research and personality tests as the “governing body” over our professional, and subsequently, personal success in life.

Whether it’s our own fault for simply being human — using our brains to over think our situation — or it’s at the hands of an outdated education system (many institutions are designing innovative solutions to this problem), the education versus work experience conundrum isn’t any easier to solve today than it was ten years ago, and this isn’t a problem we can shrug off.

A better way to learn?

In a conversation with our Executive Creative Director at Designing North Studios, Lisa Peacock, she reminded me of important conversations already happening throughout the higher-education arena, some of which are also being discussed within design fields.

One such conversation, as she explained,“How do we transform learning? Not just so young students don’t waste personal time when they set off on a pre-determined path, but also so that we can educate more people (beyond a residential experience) in the right way (experientially, via distance, collaborative learning, etc) to also solve problems that are becoming increasingly more and more complex as we evolve: the planet, our political system, racism, poverty, war, etc… If higher education doesn’t figure it out (leaving many capable minds for solving such problems behind) there will be no personal time loss to worry about — Life on this planet will be lost.”

Public or private, a university is a business; I get it; I have been a “customer” myself, and am a “customer” this very moment. Yet, the majority of the professors I have come to know well don’t teach for earning potential — they do it for the reward of working with students and serving as SMEs (subject matter experts) in their field. And to this day (seven years later) they continue to develop forward-thinking programs based on producing ‘experienced’ graduates; they are taking the education process one step further than previous generation educators, or better yet, pioneering new methods for students to overcome the challenges of adapting to what life ‘really’ looks like after school.

Should they really have to take matters into their own hands? Sure, to some extent it’s their job, but I see the corporation and executive board sharing in this responsibility with professors — adequate budget and technology tools should come with the gig. Still, when discussing the idea of introducing integrated learning programs based on real-world working demands, the common response is doubt induced by small budgets and staff.

What’s even more interesting, these professors I observe aren’t working on projects to help students determine what they are good at, and what they find most interesting about their field of study. Instead, they are asking students to physically enter the real world (business arenas across the globe, often in a virtual presence) and identify opportunities that aren’t being met or can be improved upon. From here, skills of interest can be developed into a toolkit that transcends many fields.Furthermore, they are sending their students down a “road of discovery,” where the destination provides clarity on what they ‘actually’ want to do in contrast with what they ‘believed’ they wanted to do. What a concept!

WHAT IF learning on the job was more closely connected with time in school rather than in the workforce; an internship consumed 4-5 years (across multiple disciplines) rather than just one summer. This could provide students with the time needed to make more polished decisions without being coerced into a curriculum based on traditional constraints associated with school: time, money, grades, job outlook etc…

The frustration felt by professors who fixate on a single-specialization approach must be challenging. Given today’s disruption-prone workforce, I imagine they often reconnect with past students who don’t report back with stories of success, positivity, and progression. We can’t all receive a trophy like our beloved parents once promised, but that doesn’t discredit the time and hard work educators dedicate to producing successful graduates. It doesn’t have to be this way, we can design a more successful system geared around realistic preparation.

Visualizing a model for success

Now more than ever — with the millennial generation placing greater emphasis on soul-searching — the model for a ‘successful graduate,’ ready to tackle what life has coming, must be made more clear and beneficial to the many young learners chasing their dreams… or so they think.

We must also not forget the old model — law school was a great example. It used to be common for big firms to recruit graduates from fancy programs and offer irresistible salaries while billing them out to clients. This lasted until clients realized they were paying top dollar for untrained lawyers; the model had to change thereafter, once the big firms began losing business to smaller ones who provided more qualified resources.

I believe current learning models can be shaped by making slight tweaks to experiential learning. It’s no different than the first five years in the workforce, except you get paid to try new things rather than pay to learn about what you might later want to try, and if that doesn’t work out, well too bad, pay off your loans, go back, and learn about something else you might want to try. Shouldn’t students at least pay to actively try the many/few subjects that interest them, checking some off as they go while also uncovering skills that might otherwise remain buried by the pressure of discontent and fear? This is undoubtedly what the current model breeds — just ask five random people what they do for a living, and follow that up with asking what they would rather be doing for a living. I’m confident the two answers will be in misalignment.

I call it the “pick it and stick with it” approach. It’s not working. It hasn’t worked for decades.

The constraints of time and competition are leveraged to corral pre-professionals into “choosing” their path forward in society. Again, as a current paying customer (grad-student), I see experiential learning across multiple fields to discover what makes us “tick” as a superior approach to strategic selection based on what’s realistic and in alignment with personality, grades, background, and let’s not forget, affordability — queue the phone call to dad, ring-ring-ring: “hello. “ Hi dad, I think I want to go to med school… research says I would make a great doctor.”

Experiential learning is the process of learning through experience, and is more specifically defined as “learning through reflection on doing. — Purdue University

I’m confident an institution-wide shift in mindset — with processes following behind — towards embracing discovery among students’ interests and imaginations will lead to a more effective population of young professionals entering the workforce. Speaking from what I learned along my journey, I met more people who were constantly searching for what could be, or what’s next. Very few people were excited with the present, and I attribute this to a fear of failure, a side effect to specialization too early in one’s career. Once you accept that you only fit into one small nook of the workforce, it’s easy to close yourself off from the plethora of knowledge and opportunity out there.

There’s no good reason why working and living can’t go hand-in-hand… in harmony. But hope is on the way: shiny-bright lights are beaming down through the clouds with the help of the modern-education leaders who agree with my perspective on experiencing to learn rather than learning to experience. In fact, one in particular has curated a group of professionals from a similar educational/professional background to mentor his upcoming senior class: we will be guiding them through the transition phase of student to workforce-team member, and sharing the ‘experiences’ we recorded during our journey while equipping them with the tools and knowledge we wished we had just five or six years ago — I like to call this “paying it forward,” or “sending the elevator back down.”

There has to be more to the work experience than this.

This is a thought that has been repeated far too many times in my young career. And I’m not alone on this island. In fact, the majority of my previous coworkers and current friends share this perspective, they too are spending more time ‘searching’ rather than living. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

You see, we’ve come to agree on one thing: without experiencing something you don’t know with certainty whether or not it’s a good fit. And this mindset works both ways: there are plenty of undiscovered interests and talents in this world that are hidden simply due to lack of exposure. This theory resembles the way most kids are raised in the U.S. : parents enlist them in as many sports leagues as possible, allowing them to discover where they belong, and what they can derive happiness.

When I talk with fellow peers who, like me, are living out the last years of their twenties (I know, it’s terrifying), we frequently joke about getting ‘older’ and entering the age of no return: 30 — Yikes! Mentioning this is usually followed with a deep sigh.

It’s not the hesitation of tacking on an additional year to my age that scares me, but rather the concept of time running out before I gather enough experiences to identify my ‘it’ — ideal form of professional contribution or body of defining work. I have learned about what I really don’t like and definitely don’t want to do. Looking back, I recognize missed opportunity that proved to be too “risky” at the time.

Have an open mind; allow new ways of thinking to influence the direction of your life, you will be happier person for it.

The post-college years should be a time of exploration and discovery in the professional world. Before family or a mortgage, you should feel justified in experimenting with career paths. But be prepared to fail, start over, and fail again — failure is a sign that you are actively designing. It’s OK to run into challenges right out of the gate — remember, it’s a marathon not a sprint.

At the current rate of change among companies, you will likely need to be good at many things to maintain a healthy career.

Current systems do in fact facilitate failure, and for some reason this is still viewed with negativity. Rather than manage success rates, it would be more productive to prepare professionals for what comes next: the getting back up and try something different part.

This is what you learn in your late twenty to early thirties (if you’re being honest with yourself). It’s the ‘I wasn’t expecting this part of life’ when the shortcomings of the education industry become transparent. So much is learned and achieved when the big-life plan fizzles out before it “booms,” but of course, you don’t know or understand this upon leaving the comfy confines of school; how could you?

The lessons learned during this stage of life (it really is just a phase many people experience in their lifetime) prove that you don’t know enough to pursue just one path. But for some reason society finds justification in criticizing those who don’t specialize in a single field of professional practice. This is the difference between learning in school and working in the real world: you don’t know all of the available opportunities until you are ‘in’ each unique work setting where stones can physically be turned over, and new doors opened.

For example, when I was in business school I didn’t know that I could enter the freelance economy if I choosed; I didn’t know that I could work on multiple projects at once as a consultant; I didn’t know that my education in marketing was just a foundation for a plethora of career tracks — I would still need to determine what the heck I was interested in (in the workforce), let alone good at and qualified for. And this caused significant tension — how could I become qualified for something I was advised to specialize in as a “best option,” not due to a deep interest, but rather a need to ‘simply’ pick something. And to think, I was paying to learn about a single subject I wasn’t confident I would enjoy… 100k should buy you a bit more experience, and a bit less book time — I think my fellow constituents would agree.

The truth is, you can be whatever you want to be in life, and that includes professionally; age doesn’t dictate what you can or can’t become. And figuring out what you want to be doesn’t always happen while in school; it may not even begin until entering the workforce — you just don’t know enough about the subjects you know nothing about. The elusive idea that we can excel at multiple things and build professional equity through a multidisciplinary approach is slowly becoming understood, especially as technology innovation powers full steam ahead and companies need their “rock stars” to manage numerous challenges at once.

As more and more industries transform in response to increased technology and competition, education institutions have an opportunity to follow their lead, while empowering professors to finally redesign the user experience associated with learning at a university. With this shift, learning would encompass more than subject matter, and would include the behavioral and psychological tools needed to make an impact in the workforce without regard to where you end up once the training is complete.

We are all fledglings at some point in life, but maybe a little more time in the nest would do us good.

These experiences will further train young professionals how to envision their true self, not just rely on their everyday self for answers and guidance. More importantly, they will empower students to seek multiple areas of interest, and develop a mindset that embraces transferable skills. The ultimate goal for education leaders will not be to graduate the most skilled engineers or marketing coordinators, it will be to shape problem solvers who are comfortable in many environments, and can alter their understanding of broad concepts to further absorb new knowledge. It’s this idea that will help shed more light on building transferable skills for the workplace while also exercising the human ability for rapid learning.

These are the changes we can make to fix the current education and work experience conundrum — it’s the firmware update this system has been waiting for, and it’s just in time for the arrival of smart machines. I’m not asking for a reinvention, I just want to see it designed better than before, to a level where it supports idea sharing, new ways of thinking, and most importantly, a greater value in oneself. One day, employers won’t need to evaluate education versus work experience to determine if a candidate is ‘ready’ for the gig. Can you see a similar future?

SaveSave